The official part of Christmas with my new family is over, and I have an evening alone, as the rest of them go out to shop, eat, and watch a movie, as is their usual custom on Boxing Day. We have been talking a lot about what our Christmas traditions are over the past few days, as we attempt to merge our practices and rituals, honouring what is most important to all of us. Like most of us, I have had a series of Christmas traditions, depending on where I lived and who I was living with at the time, but if you ask me what I think of when I think of Christmas, it isn’t Toronto in the 1970s or Detroit in the 1990s; it is spending Christmas in North Hatley, for many years at the incongruous Swiss chalet on a Quebec hillside house built my Gumper, my grandfather Jan Pick, and later also at our own cottage. It was always our family and my grandparents; sometimes our cousins from Kitchener joined us, and in later years, my father’s cousin Frances would come from Mexico.

What did it mean to us? It was the light in the darkness of winter. We feasted and burned candles. We skied through the woods and snowmobiled, and chopped down a tree, bringing the freshness of the forest indoors. The ornaments were battered and glittering survivors of those collected by my grandparents in their years as exiles and refugees from their native Czechoslovakia. We ate fish soup, and herring, and salmon, and eel. We ate turkey and plum pudding, and spiced beef. We ate candied orange peel, truffles, florentines, pepperkakor, vanilkove rohlicky, rum balls, Turtles, mince pies, and shortbread. We opened a mountain of presents (This was the only part my grandfather did not like — he thought we had too many presents, and he was right. And it only got worse when the Kitchener Picks joined us!). And like the Whos down in Whoville what we did most of all was sing. At Christmas Eve dinner, the apex of our feast, we would sing and sing and sing, songs in English and French; Czech, Slovak, Swedish, and Hungarian. Some were toasts and drinking songs, some were folk songs; we sang songs about the black earth of my grandparents’ homeland and about battles fought in far off Herzigovina; we sang songs my grandfather learned as a student in France and songs my mother grew up singing around a Swedish Christmas smorgasbord. We banished the darkness and drew our family together around the table. It was this family we were celebrating as we sang, especially my grandparents, especially my grandfather.

The Picks were Jewish of course, and it may be surprising for some of you to read that Christmas was so important to them. It is one of the curiosities of the ways a culture borrows from another that many Czech Jews celebrated Christmas with as much enthusiasm as their neighbors, albeit with less piety. I remember my grandmother taking about childhood Christmasses, about the carp who would come to live in the bathtub to be cleaned of its muddy interior before it would be eaten on Christmas Eve. And their family was not alone. My grandfather’s best friend from the old country was a man who survived Auschwitz and wrote a memoir of his experiences. “It was a very sad Christmas for the Jews this year,” he wrote without irony about Christmas 1939 in occupied Czechoslovakia.

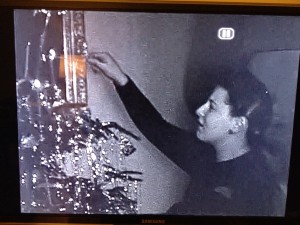

The grainy photo at the top, which shows my grandmother, Liska, lighting the candles on a Christmas tree, is a still from a movie made by our cousin Frances’s father at Christmas in 1939 in the UK. He and my grandparents and my father, Michael, had managed to escape there. Also in this film are my father’s young cousins, Peter and John, kindertransport children who had been saved by Nicholas Winton, and my great grandmother Ruzena, whose necklace I wore at our own Christmas dinner last night. The people in the film are all people I knew well, so even though the film is silent I can tell what they are saying and even what they are thinking, as they greet Father Christmas, and praise my father for riding his first tricycle. And I can see the moment when the mood grow dark and they raise a toast their friends and family left behind — my grandmother’s parents, my grandfather’s sisters, all to perish, with so many more — and my grandmother knocks back her drink, and stiffens her jaw and smiles again, prepared to defy the darkness for another year.