It has been a very long time, after all, since Jews anywhere in the world routinely wore or wielded swords, so long that when paired with “sword,” the word “Jews” (unlike, say, “Englishmen” or “Arabs”) clangs with anachronism, with humorous incongruity, like “Samurai Tailor” or “Santa Claus Conquers the Martians.” — Michael Chabon, “Afterward,” Gentlemen of the Road

When I was little and Remembrance Day rolled around on November 11, I would always be slightly ashamed and confused that neither of my grandparents fought during World War II. When I was a little bit older, old enough to enjoy looking through my grandmother’s stack of old family photos, I learned something new. Maybe nobody fought in World War II but they did fight in World War I. On the wrong side. This year, on the hundredth anniversary of the armistice, I decided to investigate.

I pulled out this photograph of my great-grandfather Oskar Bauer, and did some research. From the Verordnungsblatt für die Kaiserlich-Königliche Landwehr, Volume 37 of 1907, I discovered that at that time, he was a Kadett-Offiziersstellvertreter in the Uhlans regiment, number 4. What does that mean in English? The Kaiserlich-Königliche Landwehr was the Imperial-Royal territorial army of the Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1908, the Austrian army changed the title of cadet-officer’s deputy to that of ensign. By February 17, 1915 he had been promoted to Lieutenant, according to vol. 46, no. 17, p. 210 of the same source. The Uhlans, with the separate regiments of Dragoons and Hussars, formed the cavalry of the Austro-Hungarian army, and he was in the “Kaiser’s own” 4th regiment. Its normal home was at Olmütz, now Olomouc in Czechia, where this photograph was taken in 1914, and its composition in the same year was 65% Ruthenian, 29% Polish, and 6% “various.”

I pulled out this photograph of my great-grandfather Oskar Bauer, and did some research. From the Verordnungsblatt für die Kaiserlich-Königliche Landwehr, Volume 37 of 1907, I discovered that at that time, he was a Kadett-Offiziersstellvertreter in the Uhlans regiment, number 4. What does that mean in English? The Kaiserlich-Königliche Landwehr was the Imperial-Royal territorial army of the Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1908, the Austrian army changed the title of cadet-officer’s deputy to that of ensign. By February 17, 1915 he had been promoted to Lieutenant, according to vol. 46, no. 17, p. 210 of the same source. The Uhlans, with the separate regiments of Dragoons and Hussars, formed the cavalry of the Austro-Hungarian army, and he was in the “Kaiser’s own” 4th regiment. Its normal home was at Olmütz, now Olomouc in Czechia, where this photograph was taken in 1914, and its composition in the same year was 65% Ruthenian, 29% Polish, and 6% “various.”

In the photograph, you can see his sabre in his left hand, and on his right knee, a helmet that would have been identical to this one, and which harked back the the origin of the Uhlans as a Polish cavalry regiment. As World War I opened, the 4th Uhlans were part of the Austro-Hungarian 3rd army, under the command of Rudolf Brudermann. They were sent north into what is now Poland with the 1st through 4th armies to face the Russian army in what would become the Battle of Galicia, a decisive loss for the Austro-Hungarian forces. The Fieldmarshal and Chief of General Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf sent ten divisions of cavalry across the border to do reconnaissance on August 15th. On August 21st the 4th Uhlans met the Russian 10th Division in what was to be the largest cavalry-against-cavalry battle of the war near Jaroslavice-Wolczkowce, one of the last times horses were used effectively against each other. The battle of Galicia ended with some 400,000 members of the Austrian army killed, captured or wounded. Eventually, the Russians were able to take Przemysl, the third-largest fortress in all of Europe.

In the photograph, you can see his sabre in his left hand, and on his right knee, a helmet that would have been identical to this one, and which harked back the the origin of the Uhlans as a Polish cavalry regiment. As World War I opened, the 4th Uhlans were part of the Austro-Hungarian 3rd army, under the command of Rudolf Brudermann. They were sent north into what is now Poland with the 1st through 4th armies to face the Russian army in what would become the Battle of Galicia, a decisive loss for the Austro-Hungarian forces. The Fieldmarshal and Chief of General Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf sent ten divisions of cavalry across the border to do reconnaissance on August 15th. On August 21st the 4th Uhlans met the Russian 10th Division in what was to be the largest cavalry-against-cavalry battle of the war near Jaroslavice-Wolczkowce, one of the last times horses were used effectively against each other. The battle of Galicia ended with some 400,000 members of the Austrian army killed, captured or wounded. Eventually, the Russians were able to take Przemysl, the third-largest fortress in all of Europe.

This photograph shows my great-grandmother, Marianne Grünfeld, and it was taken in Przemysl, evidently in 1914, which was the same year their first child, Oskar “Willy” Bauer was born. She was twenty and her husband was thirty-four. Przemysl was an interesting place — on the one hand, a major Austrian fortification and barracks and so a site for the elite Austrian military to gain fame and renown, and on the other, a town that had been majority Jewish in the eighteenth century with a population that ranged from comfortably wealthy to very poor. It was still 30% Jewish by 1931, the year before Joseph Roth published his The Radetzky March. Roth’s novel haunts my reading of these events of my family’s history. It is the story of the von Trotta family, grandfather, father, and son. The grandfather was a Slovene peasant-cum-soldier, ennobled at the battle of Solferino for saving the emperor’s life. The father becomes district commander in an unnamed town in Moravia where the regimental band opens every concert with the Radetzky March. Joseph Radetzky von Radetz, the Czech-born Austrian commander for whom the march was written was, for a brief yet never-forgotten time, the commander of the fortress and town of Olmütz. The son is a lieutenant in the Uhlans regiment stationed in his father’s town, until disgrace makes him shift to an infantry regiment. He ends up in a town like Roth’s own home of Brody, a smaller version of Przemysl, with its mix of Jews, Poles, and Ruthenians, and dies in the early days of the war, when my great-grandfather fought his cavalry battle.

This photograph shows my great-grandmother, Marianne Grünfeld, and it was taken in Przemysl, evidently in 1914, which was the same year their first child, Oskar “Willy” Bauer was born. She was twenty and her husband was thirty-four. Przemysl was an interesting place — on the one hand, a major Austrian fortification and barracks and so a site for the elite Austrian military to gain fame and renown, and on the other, a town that had been majority Jewish in the eighteenth century with a population that ranged from comfortably wealthy to very poor. It was still 30% Jewish by 1931, the year before Joseph Roth published his The Radetzky March. Roth’s novel haunts my reading of these events of my family’s history. It is the story of the von Trotta family, grandfather, father, and son. The grandfather was a Slovene peasant-cum-soldier, ennobled at the battle of Solferino for saving the emperor’s life. The father becomes district commander in an unnamed town in Moravia where the regimental band opens every concert with the Radetzky March. Joseph Radetzky von Radetz, the Czech-born Austrian commander for whom the march was written was, for a brief yet never-forgotten time, the commander of the fortress and town of Olmütz. The son is a lieutenant in the Uhlans regiment stationed in his father’s town, until disgrace makes him shift to an infantry regiment. He ends up in a town like Roth’s own home of Brody, a smaller version of Przemysl, with its mix of Jews, Poles, and Ruthenians, and dies in the early days of the war, when my great-grandfather fought his cavalry battle.

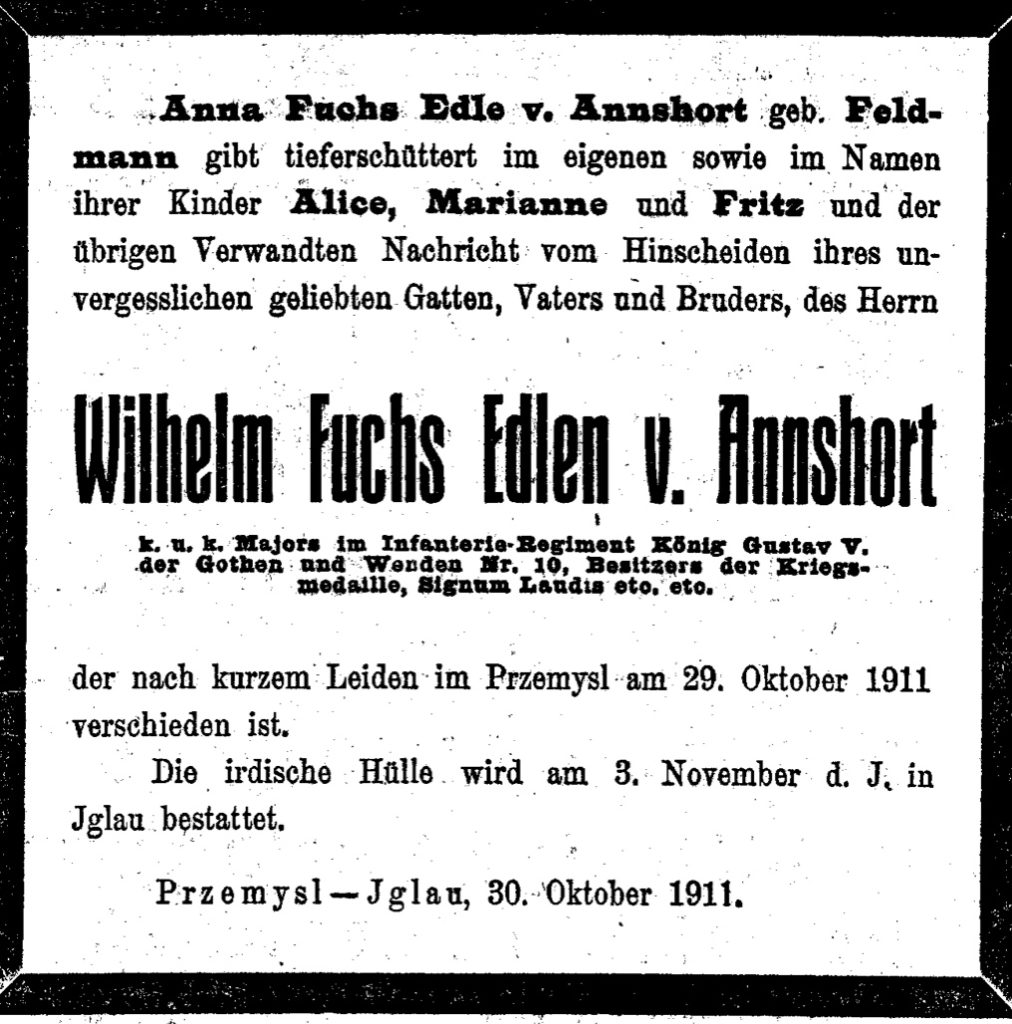

Roth made his military hero an ennobled Slovene, perhaps because he couldn’t quite imagine a Jew, ennobled for military service. But they did exist. My great-grandmother’s father died when she was only a year or so old, and her mother, Anna Feldmann, married Wilhelm Fuchs who was ennobled in 1908 as a captain, second class, in the infantry, with the title Edler von Annshort. This was his coat of arms. Note the star of David. He lived with his family in Przemysl, and died in 1911. I have often wondered what it was like to live as a Jewish noble and military family in Przemysl, on the borderline between the military elite and the shtetl. On the one hand, they were trying to assimilate as much as they could, and succeeded to the degree that Fuchs was ennobled and earned the Signum Laudis, a medal awarded to officers for military merit. On the other hand, no one ever forgot they were Jews. Marianne and her sister Alice both married army officers; Marianne and Alice both married Jews.

Roth made his military hero an ennobled Slovene, perhaps because he couldn’t quite imagine a Jew, ennobled for military service. But they did exist. My great-grandmother’s father died when she was only a year or so old, and her mother, Anna Feldmann, married Wilhelm Fuchs who was ennobled in 1908 as a captain, second class, in the infantry, with the title Edler von Annshort. This was his coat of arms. Note the star of David. He lived with his family in Przemysl, and died in 1911. I have often wondered what it was like to live as a Jewish noble and military family in Przemysl, on the borderline between the military elite and the shtetl. On the one hand, they were trying to assimilate as much as they could, and succeeded to the degree that Fuchs was ennobled and earned the Signum Laudis, a medal awarded to officers for military merit. On the other hand, no one ever forgot they were Jews. Marianne and her sister Alice both married army officers; Marianne and Alice both married Jews.

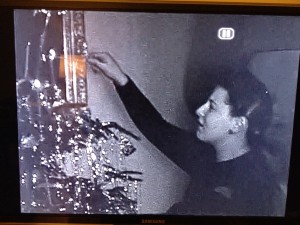

When my grandmother was a young girl, Marianne and Oskar had her baptized, still trying hard to assimilate and erase their differences with those around them. She reconverted to Judaism to marry my grandfather (perhaps the only person to convert *to* Judaism in central Europe in 1936). My great-grandparents, as I have said before here, died at Auschwitz. I don’t know when or how Marianne’s mother, Anna Fuchs Edle v. Annshort, died. I know she was alive in late 1937/early 1938 because we have a photograph of her holding my father. I can guess.