The title is misleading. The question I still ask myself is not, “When did I know I was Jewish?” but, “How, in God’s name, did I not figure it out sooner?” I blame Captain von Trapp.

I cannot remember a time when I did not know the story of how my grandmother fled Czechoslovakia, weeks after the Germans invaded, with my two-year-old father in tow, to meet my grandfather in London (the story of how he got to London, however, remained a secret until much more recently). She was a great storyteller, and in her version, she was not a bold heroine, but a foolish and somewhat spoiled girl, slightly oblivious of the danger around her. I heard many times about how she charmed the Gestapo at the border into letting them leave, how they had to stay in Versailles, and how my grandmother abandoned my father every morning to the tender ministrations of “la promeneuse” so she could hot-foot it to Paris, and later, of their life in London and Wales, of ration cards, and air raids, and shoes that unaccountably did not get polished when you left them outside your door at night. What I did not hear anywhere attached to the story was the word, “Jew.” It was a word I never heard used by any member of my family, in any context.

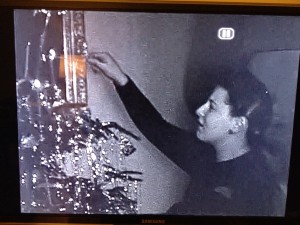

And that is where the Sound of Music comes in. I saw it for the first time a long time ago, long enough ago that I remember standing for the national anthem before it began. My grandparents had come to visit in Toronto, and we all went together. And there, on the screen, was their story, their love for their homeland, the evil Nazis, and their flight to freedom. They even lived high on a hill with a lonely goatherd, in a Swiss Chalet. In Quebec. Here it is:

When the Captain sang “Edelweiss,” my mother says, tears rolled down my grandfather’s cheeks. Bless my homeland forever.

And once again, not a mention of the word “Jew” in the whole movie (Weirdly, when you think about it. Sure, the von Trapps weren’t Jewish. But Max? Max?). No wonder I was confused as the evidence began mounting and the questions started to come. Because I knew, I knew. But I didn’t know. I read When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit and then all the Leon Uris books. I had dreams about being chased by Nazis. I even wrote a short story for school about a young girl, oh roughly my age at the time, escaping. I asked my father where our name came from. He lied (Miners from Lancaster come to work in the Silesian coal fields. I still have not forgiven him for this one!). I asked him why Gumper was smart enough to leave when others didn’t (you can tell I am getting close at this point). I asked my grandfather what happened to his two sisters. He left the room, and my grandmother changed the subject. I knew we weren’t Catholic, like all the other Czechs I knew, though when my grandfather swore, it was by Jesus and Mary (this also threw me off). Did I think they were Hussites? But no, the von Trapps weren’t Jewish. You didn’t have to be Jewish to flee the Nazis. It wasn’t a question about myself that I asked; it was one I had already answered.

Then cousin Frances came for one of the last Christmases before my grandfather and father died, and this time brought with her a family tree. On it were large branches that were missing, unknown relatives marked only “died in the war.” And Frances told us that we had a Jewish background. I didn’t fully absorb it, confused as I still was by the Captain. Maybe Gumper’s mother had been Jewish?

After my father died, my uncle sat me and my sister down with my mother and told us the story of our origins and swore us to secrecy. My mother already knew; my father had told her before they were married in an offhand way, and she regarded it as a matter of complete indifference. We didn’t keep it a secret; we started talking about our background and history with our father’s cousins, and with our grandmother, especially when we travelled with her to the Czech Republic after the wall came down. My sister remembered revealing all to our Kitchener cousins when we visited them for Christmas a couple of years after our father’s death.

For me this knowledge came, not as a revelation but as a confirmation, an “Oh, of course.” It was like I had spent my life doing a puzzle without the picture on the box, trying to piece together the faces I saw from the pieces I had. Someone handed me some missing pieces and suddenly all the sections I had been working on began to fit together. And on the woman’s face, the pieces now formed a smile.