The first source pilgrims who are interested in the history and origins of the route usually encounter is the engaging and wonderful twelfth-century Pilgrim’s Guide to Compostela. I link to the Italica Press translation by William Melczer, which is also available in a Kindle edition, for those pilgrims who would like to carry it en route. I would not suggest you replace your modern guidebook with it, however. Let’s just say that Aimery Picaud was a little optimistic when he described the length of each stage…

The Miracles of St. James accompanies the Pilgrim’s Guide in manuscripts, and is now available in its own translation. The gem of this book is its translation of the medieval sermon “Veneranda dies.” If you want an idea of how they thought of the Camino in the twelfth-century, and the origin of traditions (and complaints) that are still relevant today, this is the place to look. Exerienced pilgrims will discover many differences, of course, but I think you will be surprised to see how the more things change, the more they stay the same.

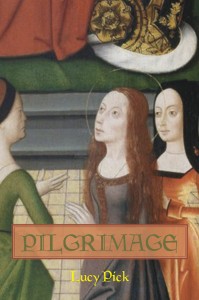

If your primary interest in the Camino is its art and architecture, and if you want to know more about what you might see along all the main roads in France and Spain, you might like Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela: A Gazeteer by Paula Gerson and Annie Shaver-Crandell. I found it an invaluable resource for imagining my heroine’s journey.

A resources designed more for the modern pilgrim, because it describes what you will see stage by stage, is David Gitlitz and Mary-Jane Davidson’s The Pilgrimage Road to Santiago: The Complete Cultural Handbook. It doesn’t provide trail directions or the addresses of albergues but it is an excellent source for explaining what it is you will actually see on the road and what it all means. I returned to it over and over again while writing.

If you would like to know more about the history of medieval Spain during the time when the pilgrimage road to Compostela was becoming popular across Europe, you could take a look at Bernard Reilly’s The Contest of Christian and Muslim Spain: 1031 – 1157. And last but not least, if you prefer some pictures while you are reading, and want to delve deeper into relations between Christians, Muslims and Jews in the peninsula, check out The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture.

Happy reading and happy walking!