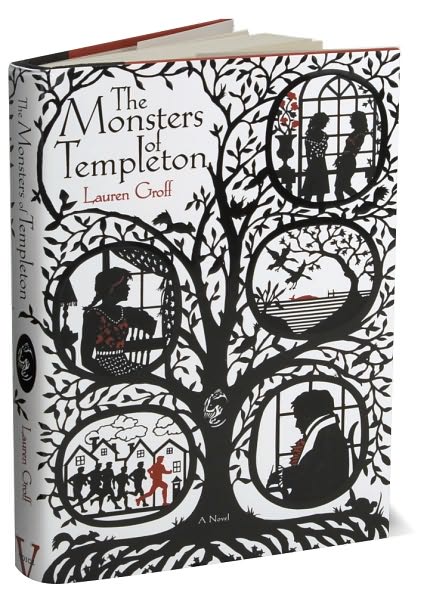

While my sister was visiting me this past week, we spent a lot of time together judging books by their covers. This cover, for Lauren Groff’s The Monsters of Templeton was one we both loved, and though neither of us bought it, I am sure I will one day soon. Almost as good as the cover is the groovy map inside. I am a sucker for maps.

While my sister was visiting me this past week, we spent a lot of time together judging books by their covers. This cover, for Lauren Groff’s The Monsters of Templeton was one we both loved, and though neither of us bought it, I am sure I will one day soon. Almost as good as the cover is the groovy map inside. I am a sucker for maps.

My sister said she prefers covers that have illustrations, and she is winning me over to her point of view. Best are covers like Groff’s, which were drawn specifically for the book. I also think of the covers for the hardcovers of Dorothy Dunnett’s Niccolo series (at least the ones I have, which were bought in Canada). In second place, and more common, are paintings and drawings that are reused as illustrations for book covers. We both enjoyed Sarah Johnson’s gallery of reused cover images for works of historical fiction. Sometimes the images were totally transformed in reuse and sometimes … well, let’s just say that certain covers could cause a lot of confusion.

Alison Pick, The Dream World

My cousin Alison’s second book of poetry was released on March 18th. I love what she had to say about it here:

My cousin Alison’s second book of poetry was released on March 18th. I love what she had to say about it here:

The Dream World was written over a five-year period during which my partner and I moved from the mainland to Newfoundland and back again. To change place is to stir up the concept of home, both real and imagined: homes inhabited, homes lost, homes we only ever longed for. Landscape is a door that opens onto desire, and many of these poems come from the struggle for belonging, in a particular location and in the physical world in general. This is my third book, and I was interested in exploring the frontiers of language, the place where words fall down in the face of the numinous, where both our feelings and what lies beyond human experience seem fundamentally unsayable. Finally, I was reading as widely as possible in the Humanities during the writing process, and I wanted to push the life of the mind up against poetry (which for me had previously been an intuitive and visceral enterprise). The Dream World is a collision of thought, feeling, and imagination, a world with borders wide enough–I hope–to encompass it all.

Eager to read more? Here’s where you can buy it.

What I’m Reading Now

Anne Enright, The Gathering

I finished this while I was on holiday in Mexico, and it wasn’t what I expected. I thought it would be a heart-warming, rollicking, tragicomic family ensemble piece but instead it was much more interesting. Veronica Hegarty’s attempts to come to terms with her family’s history after the suicide of her brother, Liam, become a meditation on the relationship between memory, history, and story and the way we use all three to endure our lives.

Liam’s death challenges the stories that Veronica uses to prop up her life, and she needs to come up with a new acount of the past. The book we read is meant not only to describe but actually, in the fiction that she has written it herself, to be the path she takes to recover lost memories and discern the fictions she has told herself from the facts she must face. It recalled the process of therapy, in which a crisis has made an old narrative unusable, and the patient, by rendering an account to the counsellor, must come up with a new version of the past that can be taken into the future. The one who can survive the strongest, is the one who can come up with the best story.

The Historian’s Craft

A colleague of mine, Catherine Brekus, once said that writing history like putting together a puzzle, only half the pieces and the box lid with the picture on it are missing. I like that analogy, and I want to push it a little further. Unlike most puzzles, the pieces of the historical puzzle, the evidence, do not fit together in only one way. The same set of pieces will be put together in different ways by different historians, because depending on our own politics, interest, background, and questions we will see different patterns on each of the pieces, alone and in series. The puzzles we make will change as generations of historians come up with new questions and approaches. There are wrong ways to put the pieces together, jamming a tab into a slot where it doesn’t fit, but also multiple right ways. Of these right ways, some will give you a better, fuller picture of the whole.

Just make sure you find the piece that disappeared under the chesterfield.

What I’m reading now

Markus Zusak, The Book Thief

This story of a young girl in Nazi Germany during World War II was the other great historical novel that I read at the end of last year, cover to cover in one go on a transatlantic flight. The most important thing I can tell you about it may be that even though the narrator tells you how the book will end on page 22, and reminds you a couple more times during the course of the book, I still had no power to stop tears streaming down my face at the end.

There are two big ideas in this book. The first is about the dangerous and beautiful power of story telling, and the way story shapes action, for better or for worse. The second, and more interesting, is about the consequences of these actions. The heroes of this book perform with the best of intentions acts which sometimes have very good ends, and sometimes very tragic. It struck me today as a result of a conversation about something quite different, that Zusak’s attention to this problem of our actions and their results may be derived from the way Hannah Arendt connects freedom to action. The characters are only free when they act, when Eric Vandenburg protects Hans Huberman from battle, when Hans gives bread to a prisoner from Dachau, when Leisel Meminger writes a book in the basement.

This book commands us to do good even in the worst circumstances, not because doing good will change the world and make it good, but because doing good and not just thinking good, knowing good, and believing good, is the only way to be free. In a culture that believes anything is possible if you only try hard enough, this message may resound as pessimistic, but I found it intensely hopeful.

What I’m reading now

Sarah Dunant, In the Company of the Courtesan.

I read a fair amount of rather middling historical fiction in 2007, trying to figure out what worked for me, why, and why not, but two wonderful novels I read at the end of the year made up for all the previous suffering I did for my Art. The second, I’ll write about in my next post (which will be soon, I promise) but the first is Sarah Dunant’s tale of the dwarf Bucino, and his life as companion to the talented courtesan, Fiammetta, in sixteenth-century Rome and Venice.

Why did this work? First of all, I felt that Dunant has an excellent period sense which is beautifully conveyed through her writing. I found the world she created entirely satisfying and convincing. I know just enough about the period to be tiresomely opinionated, but Dunant won me over from the first page. The mood she created reminded me very much of novels like Helle Hasse’s The Scarlet City or Jeanette Winterson’s The Passion.

The other great strength of this novel is Dunant’s main character, Bucino. He is a sidekick in the drama that is Fiammetta’s life, and he knows and accepts he’s a sidekick, but Dunant pulls him out of his ancillary role into the spotlight. The story is about his development as a human being, how he comes to term with the fact he is a dwarf, how he learns to love and to live for himself and not always through others, the sacrifices he makes, and the price he pays. The dramatic and exciting events that happen over the course of the novel serve as catalysts for the development of this memorable and appealing character.

Bullar

I am one-quarter Swedish, but since it is too much of a strain to be one-quarter Swedish all year long, I solved that problem by being all Swedish during the month of December. And since someone was nice enough to tell me they made the last receipt I posted, I thought I would give you another one. This one is for the lovely buns in the photo, called bullar. They may look complicated, but are very easy and all people seem to love them — children, in-laws, boyfriends, ex-husbands, step-siblings, everyone.

- 3/4 cup milk, scalded

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1/2 cup (1 stick) butter plus a few tablespoons

- 2 small tablespoons (2 packages) yeast

- 1/2 cup warm water

- 4 1/4 – 4 3/4 cups all purpose flour

- 1 tsp. salt

- 1 1/2 – 1 tbs. ground cardamom

- 2 eggs

- cinnamon and sugar

I scald the milk in the microwave in a large measuring cup and then add 1/2 cup butter cut in cubes and the sugar, to melt the butter and dissolve the sugar in the warm milk. Sprinkle the yeast on th warm water and stir. Put the milk mixture in a large bowl and add 1 1/2 cups of flour. beat with an electric mixer for a minute at low speed to develop the gluten. Beat in the eggs and the yeast. Now would be as good a time as any to add the salt and the cardamom. I always use a full tablespoon of the latter, but you can use less. Make sure it is fresh. Add as much of the rest of the flour as you need to make a nice dough. Knead for five to eight minutes, until the dough is smooth and elastic. This receipt makes a dough that is very easy to work with. Don’t add too much flour and let it get too dry, but the dough should not be sticky either.

Let it rise for 1 to 1 1/2 hours, until it has doubled in bulk. Punch it down. Divide it in two, and keep the half you are not working with under a cloth while you shape the first half. Roll one half into a long rectangle about 10″ wide and as long as it gets with the dough fairly thin, maybe 2 and a half feet long. Spread your rectangle of dough with two or three tablespoons of melted butter and sprinkle it with cinnamon sugar. How much cinnamon sugar? Well, let’s say you were making a nice piece of cinnamon toast for yourself. That much. Fold the longest end down 1/3 from the top and up 1/3 from the bottom, like you were folding a letter for a business envelope. You will end up with a piece of folded dough about 3″ wide and still two and a half feet long or whatever, sandwiching the butter and cinnamon sugar. Cut this long piece of dough into short strips that are about 3/4″ wide. Hold an end of each strip in each of your hands and twist it as many times as you can, four or so good twists. Then tie it in a knot. Yes, it will work. The first strip is the hardest, but you’ll soon get the knack. Do this for each strip and put them on a cookie sheet spaced about an inch apart on all sides.

Now you can preheat your oven to 375 degrees because you need to let each batch of dough knots rise for half an hour before you cook them. Roll, fill, fold, twist, and knot the second slab of dough while you’re waiting. Then cook each sheet for 12 to 15 minutes, until they are lightly browned on the top and bottom. And then eat them with a mug of coffee, tea, or cocoa. Dipping is encouraged. Yum.

If you are very enthusiastic, you could brush beaten egg on them and sprinkle on pearl sugar before you put them in the oven, but my family always says to heck with it. We do freeze them in bags in batches, so we can always have them fresh. I find that reheating them for 20 seconds in a microwave warms them perfectly.

Carol Shields

For my birthday, my sister gave me Eleanor Wachtel’s Random Illuminations, a collection of interviews Wachtel did with Carol, and letters Carol wrote to her, beautifully introduced in a generous and thoughtful essay by Wachtel called, “Scrapbook of Carol.” I was wary at first. Knowing too much about an author can put you right off otherwise beloved books. But I dove in. Depsite her Pulitzer and her Governor General’s award, I think she is a hugely underestimated author.

I have always identified with Carol’s heroines on some deep, emotional, slightly embarrassing and not fully expressible level, an identification encouraged by a few surface similarities, self-cultivated to a degree. I think the first novel of hers I read was Swann, given to me by my mother, and though I was not at the time, like its Sarah Maloney, a single women teaching at the University of Chicago, now I am. I have insufficient shelf space, but two copies of The Republic of Love, neither of which I can give away, because one is signed by Carol and the other, a paperback, has a photo of Fay, its heroine, exactly as I imagine her. It was only after reading it that I started photographing the stone and painted mermaids I found on travels through Europe, but now I can’t stop. And then there’s Beth, with her deep interest in medieval women saints and her involvement with —

So I admit that after reading Random Illuminations, that sickly over-identification has transferred itself to Carol as well. I am willing to grant that there may be others than just the two of us who lived life through books as children. But how many other children have thought about the peculiar problem of seeing through their noses? From Random Illuminations:

When I was a child, I used to wonder why, when I looked sideways, I could see through my nose. This was a big secret, and I didn’t tell anyone else because I kept looking at other people who had perfectly ordinary noses, without this odd phenomenon. I thought, I can’t possibly ask this question, so I lived with the mystery.

And all these years, I thought I was the only one who noticed that.

For all I learned about Carol, I didn’t discover as much that was new about her books as I thought I might But that is probably to be expected. When Wachtel asks Carol what she discovered about Jane Austen’s when she wrote her biography of Austen, Carol replies that she learned you “can’t really look to a writer’s novels to decipher a writer’s life.” It seems the reverse is also true.

Tolkien and Beowulf … in 3D

I let my son persuade me to take him to see Beowulf this weekend, and truth be told I didn’t need too much persuading when I found out that Neil Gaiman was involved with the screenplay. I’m not going to talk much about the technical aspects of the film, except that it reminded me of how my father told me a long time ago that one day computer animation would be used to make movies with lifelike people. I thought he was mad — this was over twenty years ago, we’d barely moved from Pong to Pacman (perhaps I exaggerate), and at my house we owned a Commodore 64. Some might say we haven’t quite reached the “lifelike” part, but we’re closer than I could have imagined then.

What interests me is the story. As someone who often teaches Beowulf, the poem, I was curious to see how it might be translated to film. I don’t find it an easy poem. A rare remnant of a lost cultural world, it points outward to so many vanished histories and tales that it feels incomplete. Its narrative seems episodic; the scenes with Grendel and his mother are disconnected from the final battle with the dragon. How would modern audiences respond? The first thing that struck me was that what has prepared audiences to appreciate this film is seeing JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series brought to the screen. Visualizing the world of the Rohirrim will allow audiences to accept the world of Heorot, of the Danes, Geats, and Frisians. And this is no accident since Tolkien’s Middle Earth was itself an attempt to work backwards from scraps found in Anglo-Saxon literature to a half-forgotten earlier world of elves, dwarves, and dragons that he found in elliptical and opaque fragments of ancient European literatures.

The movie is in dialogue with the poem; it purports to be the “true” story of Beowulf which the poem distorts with heroic praise. But it is a fantastical vision of truth. This is a very different Beowulf than the one we saw in The Thirteenth Warrior, the 1999 movie version of Michael Crichton’s very clever Eaters of the Dead, both of which attempt to rationalize the monsters, to give them a scientific or historical explanation, albeit in different ways. No, in this Beowulf the monsters are really real, and in this claim, I believe its authors are true to Tolkien’s vision.

Its authors are especially to be praised for the ethical question that is raised by these really real monsters, a question that is implicit in The Lord of the Rings and in almost every good guy/bad guy fantasy novel and movie, namely, what makes the good guys good and the bad guys bad, other than the fact that we are rooting for one side rather than the other? Why are Grendel and his mother bad and Beowulf good? Both sides live for violence and treasure, and attempt to kill and destroy the other. One could argue that Grendel attacks first, but his mother would probably counter that her kind lived in Denmark long before humans arrived, and since they have been hunted almost to extinction, they are the real victims. Beowulf, the character in the movie, recognizes this dilemma after the monsters are vanquished and he is at the height of his heroic reputation when he says, “We have become the monsters. There are no heroes anymore.” In a nation grappling with waterboarding and Abu Ghraib, it may be hoped this message will have resonance.

What I’m reading now

Steven Brust, The Sun, the Moon, and the Stars.

I have to admit that my interests in the fantasy genre are both specific and narrow, hovering mostly in the fairy tale end of the fantasy spectrum and branching no further afield than Charles de Lint. I started as a child with Czech folk and fairy tales, like those collected by Karel Capek, moving through Andrew Lang’s rainbow as I grew older. But I forgot about them as I entered the dull slog of adolescence — we’re too old for fairy stories, right? — until I fell upon the Fairy Tale Series edited by Terri Windling when I was in graduate school. I pounce on each one the moment I see it and I have read most in the series by now. Pamela Dean’s Tam Lin will probably always be my favourite, but there was one that proved elusive, Steven Brust’s The Sun, the Moon, and the Stars, which was also the first in the series. I finally read it this weekend.

At first glance, apart from the Hungarian folk tale about how the gypsy Csucskári killed three dragons and rescued the sun, the moon and the stars that is told in stages throughout the book, it is hard to see why this novel belongs in the series. On the surface it is a story of five struggling artists sharing a studio as told by Greg, one of their number. By the end of the book, it looks like the five are going to put on a show, and Greg has finished a very large painting. Explicitly, it is a book about the creative process and Greg’s musings on the subject are as valid for writers as they are for artists. There is more to be learned about the craft of writing from this novel than from many a how-to book.

But it isn’t a book about every kind of artistic creation, whether in words or oils, and here’s where the fairy tale comes in. It is a book that argues for myth-making, mythopoeia, a genre far less in vogue when Brust published his novel in 1986 than it is now, in our Harry Potter, LotR world. Greg isn’t just painting any old thing; he’s painting the death of Uranus, the old god, at the hands of Apollo of the Sun and Artemis of the Moon, a tale that mirrors the folk story of Csucskári that comes from Greg’s Hungarian background. Brust shows how the real life struggles of his five artists gain life and expression through the myths of tale and image.