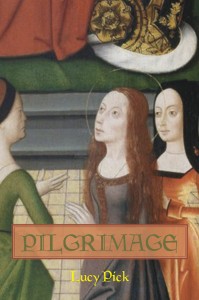

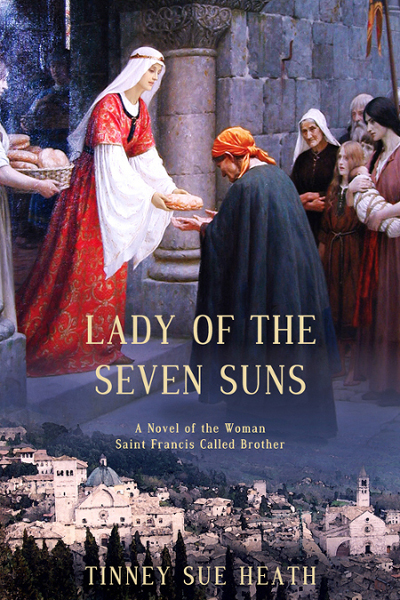

I’m delighted to post an interview with Tinney Heath about her most recent novel, Lady of the Seven Suns, about the Roman laywoman Giacoma di Settesoli and her relationship with Saint Francis of Assisi. Tinney has a background in journalism and a passion for medieval Italy. She is the author of several previous novels, including the recently re-released A Thing Done. You can learn more about her books, and join her newsletter at her webpage: https://tinneyheath.com

You set most of your writing in Italy. How did you come to write about Italy, and how did you come to be interested in the period before the plague when so many Italophiles focus on the 15th and 16th centuries?

It probably started when I was a teenager obsessed with Italian opera. I learned to speak operatic Italian, but I quickly realized it wasn’t going to do me much good, either for research or for travel. So in time I picked up some more practical Italian and finally made my way across the pond to Florence, and then I was hooked.

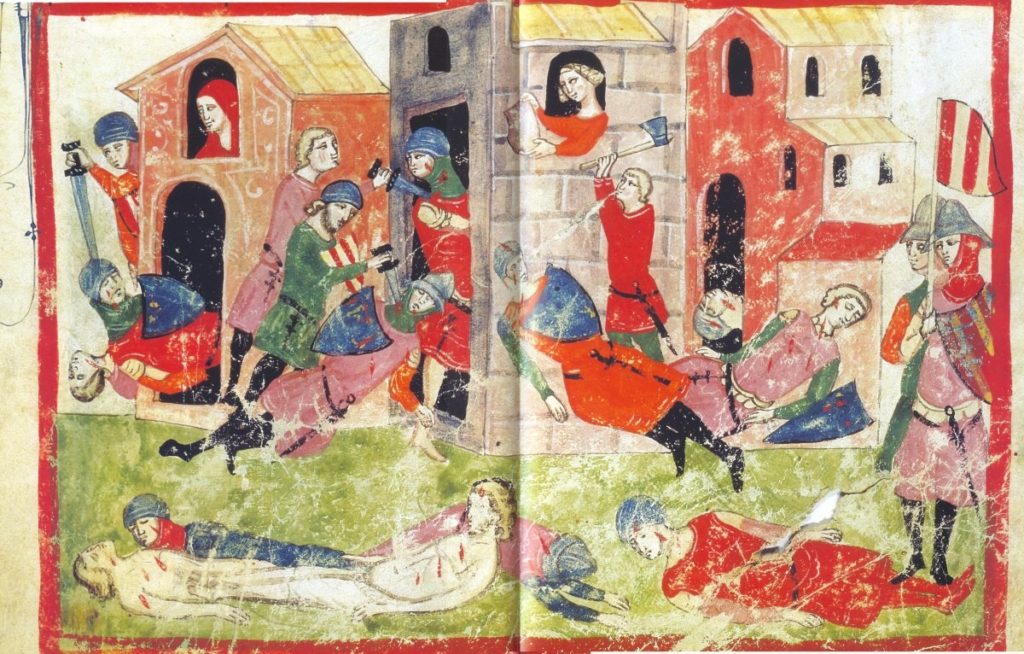

To my surprise, it wasn’t the High Renaissance of Michelangelo and the Medici that most fascinated me, but an earlier Italy, that of Dante and before. There was something alarmingly familiar in those constantly squabbling Guelfs and Ghibellines, battling each other in the streets of cities whose skylines bristled with forbidding stone towers.

Dante’s contemporaries and immediate forebears occupied a world unlike ours in many ways, and yet ours seems to be witnessing an upsurge in many of the same challenges they faced: drought, flood, famine, fire, epidemics, extremes of heat and cold, scarcity and want. And conflict. Always, conflict. Strife and contention, opposing factions jockeying for power. Fear and hatred, resentment and misunderstanding, xenophobia. Vilifying one’s opponents. Polarization. There is a certain immediacy in watching a long-ago society try to deal with these challenges, because we have only to look around us to see that despite our technology and our supposed advancement, it is all still happening. Perhaps there’s some hope in the fact they must have gotten through it somehow, or we wouldn’t be here.

You chose to show us Francis and Clare through the eyes of a third person, Giacoma di Settesoli. What drew you to her as a character, what do you think her perspective offers readers, and why have so few people ever heard of her?

I learned of Giacoma’s existence by chance, shortly before a planned vacation trip to Assisi. I was intrigued by the idea that a powerful, wealthy widow with strong political connections and control over a great deal of property could somehow become fast friends with the barefoot holy man who was devoted to Holy Poverty.

Giacoma remained a laywoman, uncloistered, able (thanks to her wealth, family status, and widowhood) to move freely around Rome and Assisi, largely unhampered by societal restraints that would have restricted her point of view. More than one contemporary account says that Francesco called her “Brother” and alludes to her close friendship with Francesco and with his other early followers.

Francesco’s friendship with Giacoma is all the more surprising because he was so cautious about dealings with women. He wrote, “Let all brothers avoid evil glances and association with women. No one may counsel them, travel alone with them or eat of the same dish with them.” And yet this is the man who, on his deathbed, instructed his brothers that the prohibition on women entering the brothers’ compound need not be observed for her.

Why have so few people heard of Giacoma? Some scholars say that her obscurity comes from the 13th century Church’s reluctance to allow Francesco’s friendship with a woman to become part of the official record. Not wanting to sanction holy men fraternizing with women, the ecclesiastical authorities chose instead to ignore Giacoma as much as possible.

In the first two Church-mandated biographies of Francesco, written by Francesco’s contemporary Thomas of Celano, Giacoma is not mentioned at all. In Saint Bonaventure’s biography, written a few years later, her role is downgraded and the story of her presence at Francesco’s death is omitted. Historian Jacques Dalarun suggests that Bonaventure “exalted Clare, the cloistered nun, over Giacoma, the lay aristocrat, in having a special spiritual rapport with Francis.”

It wasn’t possible to expunge Giacoma from the record completely. We have writings from Brother Leo and others of Francesco’s earliest followers, and they talk freely about Giacoma, just as they talk about all the others who were part of Francesco’s life and brotherhood. The best the Church could do was to de-emphasize her, and that it did.

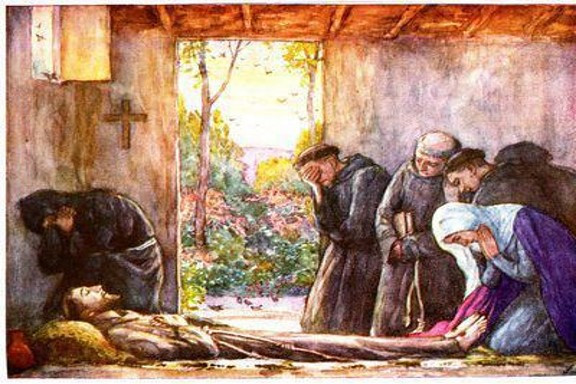

When officialdom couldn’t omit Giacoma entirely, it tried instead to emphasize the miraculous aspects of her story, thus leaving Francesco free of any suspicion. Her presence at his deathbed is a miracle because it was God who told her to go to Assisi; she was like the Magi because she brought gifts; and she was another Mary Magdalene because she mourned over Francesco’s body.

Francis and Clare are saints in the Catholic Church, and Giacoma herself is a “Blessed” — in fact (as I learned from you) her feast day is tomorrow. What were the challenges of writing a novel with broad appeal about important figures in a specific religious tradition?

Everyone has an idea of who Francesco was. To some he’s the gentle, loving patron of animals; to others, a simple man who wanted to follow in Christ’s footsteps and who was blessed with the stigmata. Many people, when asked, will start quoting from the so-called Prayer of Saint Francis (“Lord, make me an instrument of Thy peace…”), not realizing that this anonymous prayer appeared for the first time in the early 20th century in a French magazine. People of all faiths and of none revere Francesco, but most of them know very little about the times in which he lived or even about his personal history, which is more complex than all the sweetly-smiling statues suggest.

That does make it a challenge to try to depict him in fiction without offending, so I simply wrote him the way I saw him – an extraordinary man, utterly original, midwifing (sometimes reluctantly) a religious movement that had to be constantly safeguarded from any hint of heresy. I am not Catholic myself, which probably made for a steeper learning curve when writing about 13th century religion. On the other hand, it prevented me from assuming that aspects of modern Catholicism applied to the church of Francesco’s time, which was not necessarily the case.

Are there any favorite stories about your characters that you weren’t able to work into the novel?

Yes, many. For instance, there’s the story about Francesco and the wolf, in which he charms, tames, subdues, converts, befriends, and negotiates with the ravening wolf that had been terrorizing the citizens of Gubbio. He does everything but enroll it in a twelve-step program, and by the time he’s done, the townspeople have agreed to feed it and let it live in Gubbio, and the wolf, by placing its paw in Francesco’s hand, has agreed to stop killing people and their animals. (Some say the “wolf” was actually a human outlaw harrying the city.)

There’s a delightful painting by Sassetta in London’s National Gallery showing Francesco, the wolf, the people of Gubbio, and a seated notary scribbling away at their contract. Nothing could be more quintessentially Italian and medieval than that notary, who is no doubt trying to figure out how he’s going to obtain the wolf’s signature.

The other story I would love to have included was the rather bizarre turn Brother Elias’s life took after Francesco’s death, but my timeframe wouldn’t permit it. He somehow managed to go from being Francesco’s trusted Vicar General to the person entrusted with building the lavish Basilica to house Francesco’s relics (against the wishes of some of the earliest brothers), and from there to polarizing the order, serving as papal ambassador to Emperor Frederick II, getting excommunicated and thrown out of the order, and just to cap it off, riding into battle at the side of Frederick II. It’s said that children playing in the streets used to chant, “Frate Elia has gone astray, he has chosen the evil way.” (At least, that’s what they would have chanted in Guelf territory.)

Elias’s whole unlikely trajectory is fascinating and would make a wonderful novel. I’m not going to write it, but if somebody else does, I’ll definitely read it.

Thank you, Tinney! So would I! And I am looking forward to more books from you.