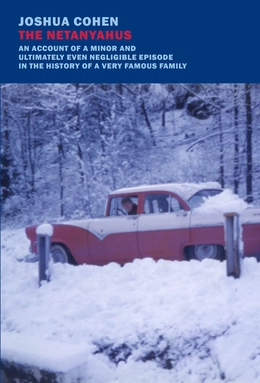

My uncle died last week. He was the Canadian-born second son of his family of Jewish refugees, his parents and my father, who made their way from Czechoslovakia to Sherbrooke Quebec in the middle of World War II. I should be writing a eulogy for his funeral next weekend, but instead I am writing this, even though I haven’t done a review here in years, and everyone else who wanted to, read this book when it first came out and is finished with it by now. I should review Flora Carr’s The Tower, about Mary Queen of Scots in prison, which I read around the same time and liked much more. But I woke this morning at 5am, stewing about The Netanyahus, and I want to get it out of my system.

The novel purports to be a fictionalized account of an anedote supposedly related to the author by Harold Bloom, about when Ben-Zion Netanyahu, scholar of the Spanish Inquisition and father of the current prime minister of Israel, came to Bloom’s campus for a job talk, and Bloom was pressed into shepherding him around. Netanyahu’s wife and three young sons came along and hijinx, we are told, ensued. I have questions.

The book by turns amused, irritated, and puzzled me. At the level of the sentence and the scene, Cohen is a remarkable writer. The first chapters are set-pieces, each capable of standing alone as an evocation of postwar Jewish America (I guess. It’s a world I know only from other novels). I especially liked chapter 4, Rosh Hashanah 1959, which has the feel of a one-act play. Harold Bloom has become Ruben Blum welcoming his in-laws with his wife and daughter; Yale has become a mid-tier college in the wilds of western New York. But none of this is new ground. We are even given a dream to analyze. We’ve read these books, we’ve seen these movies.

The first jarring note is a letter of reference, sent by a colleague of Netanyahu in Israel, urging him to please, please not hire him. The second is the arrival of the Netanyahus themselves. Both confront us with the problem of Israel in its politics, as the colleague warns us that Netanyahu is one of those Bad Zionists, not like the others at Hebrew U who are Good Zionists, and also in its stereotypes. The Netanyahus embody in every respect all the worst stereotypes North American Jews have about Israelis (though there’s not one character in this novel who isn’t a sterotype). But if Cohen wants to show us how Ben-Zion’s Revisionist Zionism and its connection to his belief that the Spanish Inquisition shows Jews can only live safely within Israel formed Benjamin, this message gets lost in the pratfalls and slapstick foibles of the family. Ben-Zion’s “job talk,” a condensed version of of his 1400 page The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth-Century Spain, is left unanswered, standing alone. We end by disliking and despising the Netanyahus at the end because they are rude and crude and icky, not because they are wrong. But they are wrong.

I said the book puzzled me. It was full of unaccountable errors. My hackles went up when Blum’s chair described Netanyahu as a historian of Iberia. Admittedly, this is a personal bugbear but no one would have described themselves in 1959 as a historian of Iberia; they’d have said Spain. Maybe Cohen doesn’t get all the nuances of my field, fine. But there were more errors, and they get more and more impossible as the book goes on. It snows for three days straight in the lee of Lake Erie for a total of six inches. That’s it? An assistant professor buys a colour TV? In 1959? Other readers noticed different anachronisms, brands that didn’t exist, suitaces with zippers. Authorial carelessness? I don’t think so: Netanyahu confuses Torah with Tanakh, saying the former is the Christian Old Testament. Discussing the invention of new Hebrew words for new technologies he gives the verbs for “telephone” as l’talphen, metalphen, and metalphenet. They’re l’talpen, metalpen, metalpenet. Netanyahu knows all this and Cohen does too. The last straw was when, at the reception after the talk, in honour of Netanyhu’s work on “the Iberian Peninsula” they are fed paella, manchego, and … jambon. Not jamón but jambon. Leaving aside the challenge of getting manchego and jamón in 1960 western New York (but not leaving aside the notion that they would serve ham at a reception for a Jewish speaker, which is completely plausible), Cohen certainly knows one word is French and the other Spanish.

So what’s up? Any why has almost no one noticed any of this in a book that won a Pultizer prize and a National Jewish Book Award? That’s the real reason I’m writing this review; i want to know. the answers to both these questions. Are we playing with fictionality here, is that it? And if so, why should I, as most readers do, take the final chapter, labelled “Credits and Extra Credit,” as a truthful authorial afterword? Why should I take his account of his friendship with Bloom, and the recounting of the anedcote that became the novel as anything more than another fiction, especially since a different reviewer found incongruities in that story too?

Oh, and it’s a Christmas novel. No, really. It’s never going to be the subject of an ecumenical Hallmark movie, so here’s a picture of my family instead, not in 1959, but in 1967, which is pretty close. My grandfather may be holding the camera. I was probably having a nap. My uncle is standing.