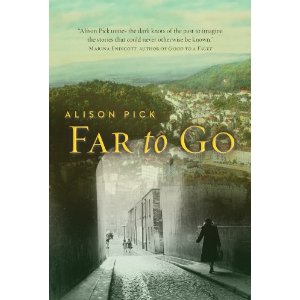

My father died in July 1987; my uncle told us about our Jewish background that same summer; in 1989 the Berlin Wall came down, and in June 1993, my sister and I went to Czechoslovakia (as it still was then, though not for long) with my grandmother, Liska. Travelling through Prague and the Czech countryside with Granny was like listening to Marcel Proust. We would turn a corner, she’d see a building, and the stories would pour forth. A visit to the the Kinsky palace, in Chlumec where my great-grandparents had lived, reminded her of how when they’d pass it on their weekly drive between Prague and Hronov, my Gumper would tease, “Don’t look up. The Count will invite us for lunch, and we just don’t have time.” In the Prague Castle, we saw the Spanish Hall where she went to a Red Cross Ball then, “That’s the Schwartzenburg Palace,” she exclaimed before one sgraffitoed building, and told us how it used to be the Swiss embassy, and how she had gone there to beg (successfully) to have her Swiss visa extended, though she did not yet have her exit permit from the Gestapo. To get the permit, her father bribed a high Nazi official who came to their house and was “decent to them” and gave her the right permit. All my photos of this trip show my sister with her arm around my small Granny, holding her and protecting her.

We went to the farm where she grew up in Herelec, and the second floor apartment on Anny Lekenske street in Prague, where she moved with her parents and brother. And a lot of the stories she told were about her parents, especially Marianne, her mother. Marianne was born in 1894 in Jihlava, or Iglau as it was called then. Her father, Julius Grünfeld died the year after she was born and her mother, Anna Feldmann, remarried a man named Fuchs who had been ennobled with the name Fuchs-Anshort. It seems that Marianne lost contact with her father’s family, but just in the past year my sister and my niece have been able to reconnect with a branch descended from Julius’s oldest brother. They…look like our cousins! Which they are.

Marianne’s step-father was an army officer, and moved the family to Przemysl. Now part of Poland, it was then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where it was a crucial crossroads for trade, and a strategic barrier against the Russians. Some of the most important battles in World War I were fought there. It was also home to an ancient and substantial Jewish community, which formed a third of the population of the town. There, this ennobled sophisticated family, whose livelihood depended on assimilation to the norms and values of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its military, encountered, perhaps for the first time in large numbers, the Ostjuden, whom they would have seen as threatening and strange. It is perhaps this experience that best explains Marianne’s indifference, or perhaps better, hostility, to her Jewish background. The nineteenth-century emancipation of the Jews was not just an emancipation from the punitive restrictions of the state; it was also, for those who chose — and the families of both my father’s parents did so choose — an emancipation from the rabbis. Her son, Willy, was not circumcised at birth (and, poor boy, medical problems caused him to have to undergo circumcision as a youth). My grandmother’s name was entered in the record of Jewish births in Iglau, but the same document also records her abandonment of the “israelische religion” at the age of three to become a Catholic. Granny showed us the church where Marianne encouraged her children to participate in the Ascension day procession, and she told us how a crew of thirty Slovaks would come to bring in the harvest in the autumn. They wore their national dress on Sunday and to her mother’s delight, made grain crowns for the family, which they would keep safe until the following year. These folk customs delighted Marianne, but she showed no interest in her own tradition. Moreover, she identified herself with the traditions of Austria, not this new country of Czechs. Granny showed us the old Deutsches Haus in Prague where Marianne would go to meet friends. “Of course,” my grandmother then said under breath, “They all became Nazi collaborators.”

My grandmother loved her mother; you could hear it in her voice. The photos show them smiling together like sisters, my grandmother a little shorter, plumper, and more ordinary-looking than her elegant mother, but raised to be strong, and to value herself. I have a few things that belonged to Marianne: the family portraits that were passed down through the daughters of the family, her handwritten recipe book, a pair of earrings — chased gold lozenges, each inset with a pearl. My grandmother loved clothing, and she loved to go shopping, a trait she passed down to her granddaughters, though she wasn’t interested in labels, and she despised the boutique-ification of women’s fashion (one of my favorite stories about my Granny was her tale of walking into a Valentino boutique and picking up some of the garments, whereupon the salesman rushed up to her, distressed that she was touching the clothing. “Madame,” he said, “You mustn’t touch. If you want something I will help you. This is haute couture, you know.” Granny turned to him and said, “THIS is not haute couture; THIS is prêt-à-porter,” and stormed out of the shop.) When she died, we divided up her clothing, and one of the pieces I chose was Marianne’s alligator purse.

On December 14, 1941, Marianne and her husband Oskar were sent to Theresienstadt, and on January 20, 1943 they were sent to Auschwitz, where they perished. They had visas for Cuba, but Oskar said, “What do I want to do? Live in a hotel for the rest of my life?” and they did not go. My grandmother spoke to a survivor of Theresienstadt after the war who told her the last time he had seen her mother, she was smiling and taking care of the chickens. “And that is how I always like to think of her,” my grandmother said, voice shaking,’Smiling and taking care of the chickens.”